Sony hired Adam Wilt and me to go out and shoot some 4K imagery with an FS700 and write up our experiences, which we presented at CineGear 2013 in Hollywood. This is my half of the presentation.

First off, you should know that Adam has posted his side of the presentation here. He tends to focus in depth on technical issues and workflows, and he’s way smarter than I am at that kind of thing. He’s also more detail oriented: I get a little ADD when I have to go into that much depth about a technical subject.

I excel at talking about actual usability: How is it to work with? What is it good for? What is it bad for? What are the “gotchas”? What do I really need to know to get the most out of this camera in a production environment? This is my side of the story.

Modern film industry newbies are overwhelmingly focused on gear. They want to know what gear will make them a filmmaker. As a seasoned professional I can tell you the answer is this: “The gear you have access to.”

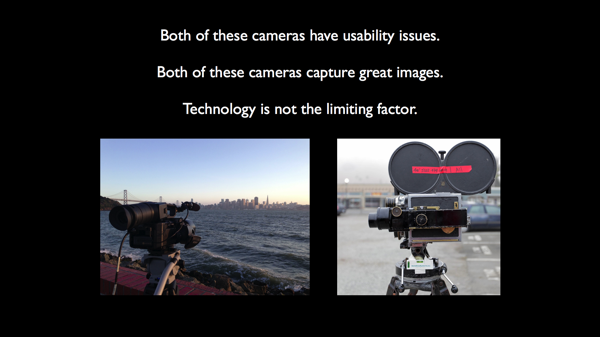

The Sony FS700, seen above at left shooting the San Francisco skyline, creates gorgeous pictures. It’s not the fastest camera in the world to work with and, unless you have a 4K monitor handy (or at least a really good HD monitor) you’ll have no idea what you really got until you view the footage later in a controlled environment.

The camera on the right is a Bell & Howell 2709 silent film camera. This picture was taken when I got roped into assisting on a silent film project shot by the Niles Silent History Museum in Fremont, CA. (I haven’t assisted since 1992, and I don’t do it professionally, but since the project already had a DP and the operator was the only one who knew how to hand crank the camera at the right speed, I offered to assist. It was a great chance to touch film again, and it brought back a lot of memories. Best of all I found that after more than 20 years I still know my way around the inside of a changing bag.) There’s no way to see directly through the lens while shooting, you can’t see an image until the film is processed, and there are a good many ways to screw up the image and not discover this until you see dailies. And considering black and white dailies take two to four weeks to be processed these days any mistakes made on set are going to haunt you for a long time.

There are 28 things an assistant is supposed to do to this camera before every take. In practice there are really about ten that absolutely need to be done every single time, but miss one and you’ve killed a shot… or maybe a series of shots on the same roll of film.

In spite of this some of the greatest movies in history were shot on the Bell & Howell 2709 by cinematographers and their crews who knew the camera’s limitations and worked within them… and every once in a while found ways to push themselves a little further. In this sense the FS700 is equally capable: if you know what it can do and use it for what it’s good for, you’ll make some amazing images.

The trick is know where you can’t cut corners. For example:

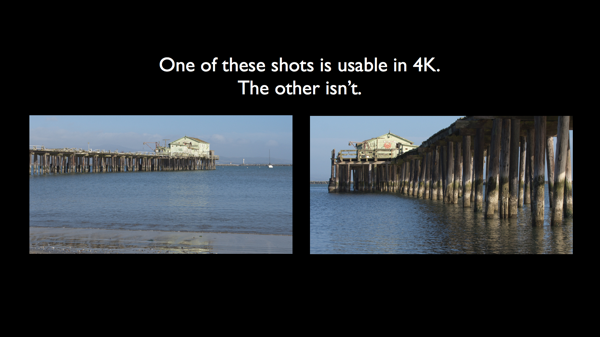

I captured the shot on the left after ignoring Adam’s advice to always open up the f-stop on the lens before focusing. I did this because opening up the stop on an FS700 is a pain when using still lenses as you have to crank in a ton of ND and then spin, spin, spin the aperture wheel to bring exposure back to the point where you can see something to focus on. This takes 10-20 seconds per shot, and sometimes I just want to get the shot and move on–or grab a shot before it goes away. I learned the hard way, though, that this is a shortcut you can’t take with the FS700.

The shot on the right was taken using Adam’s method (which is the correct method):

What may be hard to see at this resolution is that the shot on the left, that I focused by eye at f/11 against Adam’s advice, is slightly soft. It’s too soft to use in 4K, where the goal is to make everything really sharp to take advantage of the extra resolution. The focus is only slightly out, but it’s really noticeable in 4K. The picture on the right was focused at f/2.8 and in 4K it’s tack sharp.

So… why did this happen?

In 4K you really need to make sure something is in sharp focus at all times or the image will look soft overall. Focus splits under such circumstances make me very nervous. If the most important thing is in focus then it’s no big deal to try to hold other things in focus as well, but at least you’re safe if your focus split fails. It’s best to pick a single point of focus and make sure it is sharp.

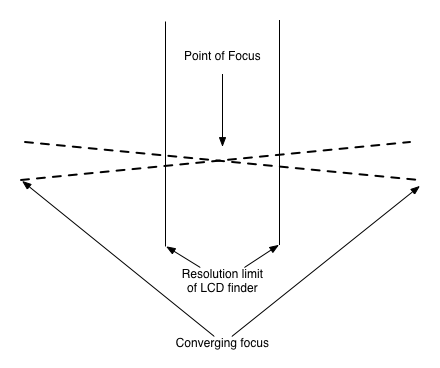

The diagram above shows focus converging on a single point of focus (dotted lines) and the limits of the on-board LCD finder resolution. Notice how the the depth of field outside the LCD resolution limits converges gently, not dramatically. This is what happens when you focus with a lot of depth of field (say, at f/11).

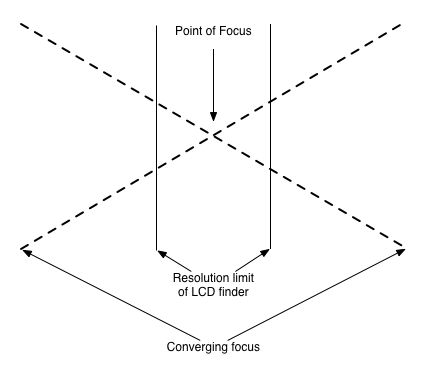

This diagram shows you what happens when you open up the stop (to, say, f/2.8). Focus converges much more dramatically, so even if you still have some slop within the resolution limits of the on-board LCD you can still see focus as it “snaps” in. At f/11 it’s easy to roll focus around and not see much of a difference in the on-board LCD, but you’ll see a huge difference when you watch the shot in 4K. At f2.8 you’ll see definitely see the point of focus much more cleanly. I never lost a shot opening up the lens all the way to focus.

Oh, and if you’re using the FS700 with still lenses, as you most likely are as the FS700 is the “budget” 4K camera, you can’t zoom in, focus, and then pull out the way you can with real cine zooms. Cine zooms are designed so that focus tracks during a focal length change, but still zooms are not. If you do zoom in to focus on a still lens and then pull out again to grab your shot you’ll most likely find that the shot is soft.

Point by point:

- Still lenses have small barrels with focus markings that are approximate only. This makes it impossible for a camera assistant to focus by the numbers. Cine lenses have bigger barrels and very precise markings so that an assistant can find 9’10” very, very quickly.

- Still lenses are not designed for manual focus. The difference between focus at infinity and focus just in front of or past infinity is approximately 1/2 of a gnat sneeze. Unless you have several gnats and handful of pollen it’s going to take a long time to dial in, with shaky hands, the exact point on a still lens where infinity is in focus.

- Still lenses are very sharp. You’ll never see that sharpness when shooting in the field.

- As well as opening up to the widest f/stop for focusing, use pixel-for-pixel magnification mode as well. If you do this your images will be sharp. If you don’t do this they most likely won’t be.

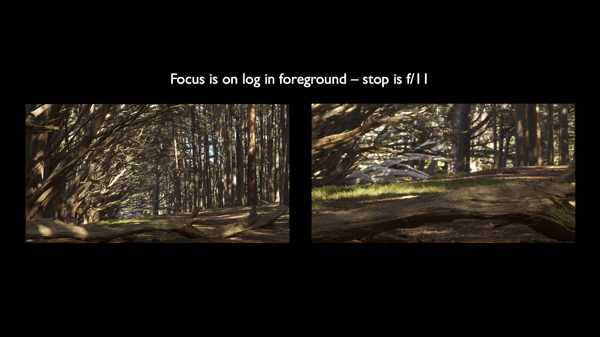

Here’s an example of what happened when I tried to play a focus split:

It’s hard to tell in this small an image, but what I’m trying to show is that the log is the ONLY thing in focus. (Everything looks sharp on the left, but on the right the background is noticeably soft. When projected in 4K the background of the lefthand picture looks soft as well.) Splits work in HD, but not in 4K.

A note about 4K projection vs. 4K monitors: I don’t know if it’s because there’s so much detail compressed into a smaller frame, but focus seems much more critical on 4K monitors than it does in projection. Projected images still need to be noticeably sharp, but 4K monitors make everything look a lot sharper. Don’t think that shooting for 4K broadcast will be easier on your camera assistant, because it won’t.

The point of shooting in 4K is to take advantage of the extra resolution, so it makes sense to use sharp lenses set to an f/stop that falls within their sharpest range (usually f/4-f/11).

Next: Framing, Gamma and more…