The answer is not as sexy as you think. It boils down to being curious, asking lots of annoying questions, and never assuming I know the real story.

The answer is not as sexy as you think. It boils down to being curious, asking lots of annoying questions, and never assuming I know the real story.

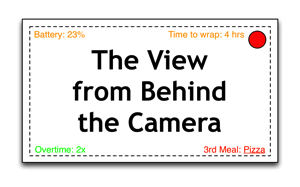

On a recent shoot in a distant city the data manager saw me going through all the monitor menus and scrutinizing every setting. “Aha!” I said, discovering that the monitor gamma was set to “Varicam” instead of “Studio/Preset”. A few seconds later I found myself changing the color space from SMPTE-C to Rec 709 and turning off the excessive sharpening dialed in by the previous user.

“That’s right,” said the data manager, who’d read some of my articles, “you’re some kind of color expert, aren’t you?”

This always floors me. Such compliments are flattering, but I don’t really think of myself as an expert. I just ask a lot of questions because motion picture technology is complex and I don’t want to screw something up. The more answers I get the more questions I learn to ask. And, it turns out, there’s an endless amount of stuff to learn these days.

First I became the camera expert. When the RED ONE was released I wanted to be at the top of the list of “DPs who knew the RED ONE intimately.” I spent a lot of time hanging out in rental houses with video engineers looking at test charts and playing with color and exposure. It was a fascinating education, as glitches in color and exposure that I assumed were the result of hardware design choices disappeared with new software builds.

For example, early RED ONEs showed dramatic color shifts in highlights when one color channel clipped. Under tungsten light highlights became cyan when the red channel clipped, and yellow under daylight when the blue channel clipped. One software build later that issue was gone. “How can this possibly be?” I said. “How is it that this one camera does this one thing that no other camera does, and it’s fixable by software?”

“All cameras do that,” I was told. “They just hide it better.” My education as to how cameras work was built on watching the RED ONE assembled, in software, right before my eyes. I learned all the issues that other camera manufacturers had been dealing with for years and had kept carefully hidden from me, the end user.

Over time I discovered that knowing these little foibles allowed me to understand what was happening under the hood of any given camera, so that when something failed–a highlight shifted color or solarized, for example–I had a very good idea of what was going on. As a cinematographer it was a bit like watching a film stock built from scratch: once I understood the process I was better able to understand, generally, how all film stocks (cameras) worked and–occasionally–failed.

I read on someone’s blog that the RED ONE had an IR leak that reared its head when using ND filters heavier than .90. I immediately tested this, discovered it was true, and wrote a series of articles on the subject. I’d never dreamed that this was possible, and I was fascinated by this little window that had opened into the world of sensor design. I discovered that different cameras required different types of supplemental IR filters, and that some filters worked better than others. I also learned, at a very basic yet deep level, how filters worked overall and in what parts of the spectrum they were normally effective.

Suddenly I was the IR expert. I’m not sure how that happened; I just saw something interesting that, in my previous world, was not supposed to happen. I asked a lot of questions and wrote a lot of articles.

I’m not sure where I’m headed next. Currently I seem to be the “color expert,” simply because I’ve been writing a lot about color science and comparing cameras to each other, but I really know nothing in depth about how color works. The math is beyond me, and there’s a reason that the average color scientist has some sort of advanced degree: it’s really, really complicated stuff. But, as my friend Adam Wilt says, “In the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king,” and I guess that there are a couple of areas in which I’m the one-eyed man. I’m also wearing sunglasses, squinting and staring into the sun, but I’m not as blind as I used to be–and I seem to know a lot more than most.

I many DPs and DITs who go blissfully about their business not knowing anything about how their tools really work. Many of them create very nice pictures. Occasionally their lack of knowledge bites them, but you don’t really have to be a technical whiz to succeed artistically in this business. It does keep you out of trouble, though. There’s a lot that can go wrong technically on a set and in post, and some of those things can result in a costly reshoot and a lot of tears shed by a producer with money on the line.

Ultimately I just want to be an artist and a craftsperson. Artistry is largely self expression, but craftsmanship requires knowledge, skill and practice. Craftsmanship makes artistry possible. I like to know how my tools work so I can craft the best images I possibly can, and try to head off all the distracting disasters that lurk around the corner of every production.

That brings me back to setting up monitors. In the video world we have to see what we’re doing as cameras are somewhat unpredictable: they can be set up in a nearly infinite number of ways, and each setting has positive or dire consequences. When a monitor is your only real means of quality control it seems like a good idea to make sure it’s set up correctly. It seems every Panasonic monitor I come across, for example, is set up for Varicam “Film Rec” gamma, but as Varicams are all but extinct it doesn’t seem like a good idea to view footage from other cameras through an obsolete gamma setting. Just as often I find the color space is set incorrectly (EBU or SMPTE-C instead of Rec 709) or the white point is off (D93 instead of D65, for example).

All of this impacts not only how I light and expose a scene, but it impacts how my clients perceive my work. I shot a project a little while back where the client ordered one monitor, but then decided they wanted a second one placed in another room for the agency to watch. My camera assistant had a spare in his van and set it up for them.

At one point someone from the agency came to the set, looked at the director’s monitor and said, “Wow, the picture looks much better out here!” I walked, quickly, to the agency’s viewing room and discovered the monitor gamma was set incorrectly (“Varicam” again!”) and the image appeared way too bright with clipped highlights. Changing that one setting restored their confidence in me.

I don’t think I’m an expert. I’ve learned enough to know that I’ll never know it all, and I’ll never stop learning. I do know, however, that I know a lot about many different things, all of which are crucial to keeping my job. No one cares that I know all of this when they hire me, as I get jobs based on my reputation and the quality of work that I show. My techie-geeky knowledge doesn’t get me work, but it does ensure repeat business when nothing gets screwed up technically. I get work based on my reel; I keep working because I can recognize when a monitor is messed up and then figure out how to fix it so my client doesn’t panic.

I didn’t set out to be an expert. I just wanted to understand how my tools worked so I could use them effectively without making costly mistakes. It turns out that such knowledge is a black hole, and once you fall into it you never stop falling. And that, for me, is a lot of fun.

Share.