I’ve always wanted to test a camera’s dynamic range by beautifully lighting a room using one punchy light placed outside a window. I finally got my chance.

When RED released the Epic with HDR I eagerly sat through their “Red Dragon” promotional NAB screening, waiting for an amazing image that would show me how this technology would forever change my life. Sadly, I saw nothing at all that demonstrated the full power of HDR. There were not obvious HDR shots at all. I learned later that there was one HDR’d shot, looking into some lights along a staircase, but the lights were flat and featureless and HDR revealed no additional detail… because there wasn’t any additional detail to start with.

The piece was beautifully shot under what was obviously very low light, but in conditions that would work well for just about any camera. Shooting wide open on a lens generally results in lower contrast, and the lack of textured highlights prevented assessment of the camera’s ability to capture and retain highlight detail. “All they had to do,” I thought, “was light one set with one big light placed outside a window. Show me that the camera can hold detail in the curtains while the ambient bounce illuminates the rest of the room.”

Recently Sony sent Adam Wilt and I an FS7 to play with, and we rounded up some colleagues with the goal of shooting exactly this test. One of my regular gaffers, Tom Guiney, offered his house as a location, and three of my CML cohorts (Adam, Alan Hereford and Dan Drasin) stepped in to help. Dan brought a friend’s daughter, Jessica, to be our model.

Here’s the video. It’s best to watch it in HD:

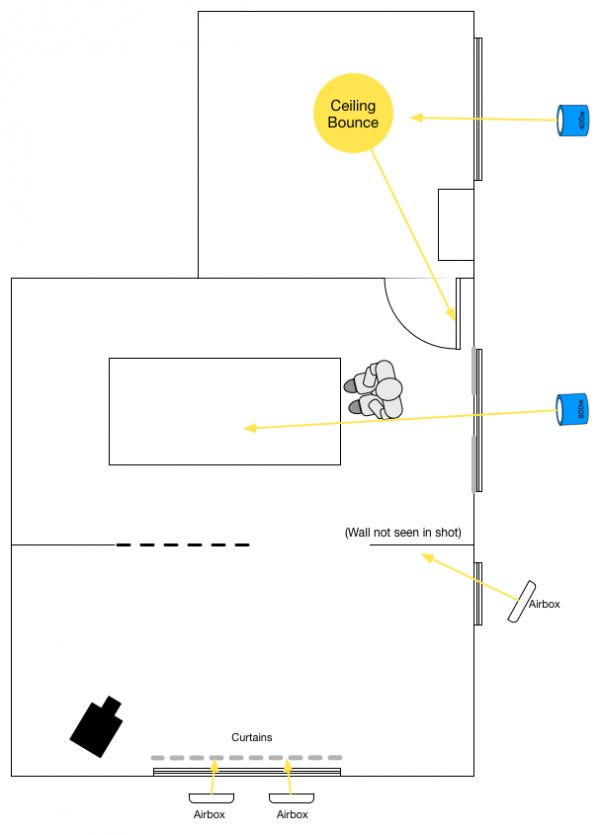

We shot three setups in one night, but I’m only going to focus on one in this article: the dining room.

My goal was to light the dining room with a single light, although we used additional units in the kitchen and outside the living room. Tom placed an 800w HMI PAR about 7′ away from the dining room window, and I asked for a very narrow lens as I wanted as much bounce off the table as possible.

The kitchen, seen through the open door in the background, needed some work so we bounced a 400w PAR off the ceiling from outside the window that was over the sink. The hot spot on the ceiling lit the area around the sink nicely but fell off toward the dining room door, so while the light was very soft it had some directionality: we can sense that the light striking the background door is coming from the kitchen and not from within the dining room.

Tom Guiney is the owner of AirBox Lighting, a company that builds inflatable softboxes for LED lights. They look like inflatable pillows made of half soft frost, and they strap onto the front of all common LED panel lights. The foreground door looked to be devoid of glass, so we put two AirBoxes outside Tom’s living room window to make its curtains a glow. Their reflection makes reveals the glass in the door and adds some texture to the shot, while also conveying the sense that the scene takes place in daylight.

We shot at night for total control, and without the reflection of the curtains in the glass the door felt way too dark… but I needed something dark in the frame so I could observe how noisy dark tones are at different ISOs.

Although I’ve shot formal dynamic range tests in the past with the FS7, I wanted to see how it did in a real environment. The FS7’s “native” ISO is 2000, but I’ve felt more comfortable rating it at 1000 for most of my work. I opted to try it out at 1000, 2000 and 4000, one stop over and under its suggested ISO.

We recorded both internally, to XAVC-I, and externally in DNG format to a Convergent Designs Odyssey 7Q. XAVC-I is the same XAVC flavor you’ll find in the F5 and F55; the I stands for “intraframe,” meaning the compression algorithm works within one frame at a time. The FS7 introduces a different flavor of XAVC, XAVC-L, a long-GOP interframe compression scheme that stores information common to a “group of pictures” (GOP) and thereafter stores only the changes between them. I’ve had issues with long-GOP compression schemes in the past, particularly around areas of high contrast (specifically green screens) so I tend to lean on intraframe codecs when possible. I’d shot XAVC-I on the F5 and F55 so I knew it well enough: while I’d never use it for green screen (it does not do high contrast edges well!) it works fine for nearly everything else.

We ran into a bit of a problem with the Odyssey, which at the time only supported SGamut/S-Log2—and I wanted to shoot SGamut3.cine/S-Log3. SGamut is Sony’s original color space and it distorts hues in ways that bug me: reds shift toward orange, yellows are extremely saturated (to the point where it was almost impossible to shoot a sunset without the sun turning into a lemon ball surrounded by black edges), blues skew toward cyan. (I wrote an article about those differences here.)

SGamut3.cine’s color is subtle, elegant and accurate, and is a very different look to anything I could create in custom mode. In fact, I refuse to shoot the F5, F55 and FS7 in any mode other than Cine-EI, and SGamut3.cine and S-Log3 are the reason. Add in the LC709 Type A LUT and I end up with a look that is… well, for want of a better way to say it, NOTHING like a traditional Sony camera. Now that film has all but disappeared, primarily due to cameras that focus on looking more filmic than electronic (Alexa and Epic come to mind), there’s tremendous pressure on traditional video companies to step out of their comfort zones and embrace looks that are not what they’ve traditionally delivered. Sony has done a great job in delivering SGamut3.cine along with several interesting built-in LUTs. LC709 Type A is my favorite.

As the Odyssey didn’t offer SGamut3.cine/S-Log3 as an option, and I didn’t want to shoot SGamut, I opted to shoot SGamut3.cine/S-Log3 while telling the Odyssey it was receiving SGamut/S-Log2. The deck performed perfectly, and played footage back properly, but what we thought was a simple metadata tweak in post turned into a little bit of a nightmare. More on that later.

One interesting note: the Odyssey was the only method by which we could play back footage and have it appear anywhere close to “normal.” The FS7, F5 and F55 are not physically able to apply a LUT when playing back from internally-recorded material: you can see the LUT while setting up and while shooting, but on playback you’re going to see a flat log-encoded image in the wrong color space. This is not an issue with raw recording as the Sony R5 raw deck WILL apply a LUT on playback.

FS7 color is very accurate to what I see by eye, if a little less saturated. It’s certainly not the video look that I’ve equated with Sony in the past. The F55 is a better looking camera, but that’s because it shares a color filter array design with the F65. The FS7 shares a CFA with the Sony F3, so color is a little less subtle and sophisticated but still pleasant. (In 1980s and 1990s video terminology, I think of the FS7 and F5 as “industrial” cameras and the F55 and F65 being “broadcast” cameras. Industrial cameras were cut some corners for affordability’s sake while broadcast cameras were top of the line in color, processing, dynamic range and build quality.)

Enough background material: let’s look at some pictures. All images were captured out of Sony Raw Viewer unless otherwise noted. Click any image to enlarge it.

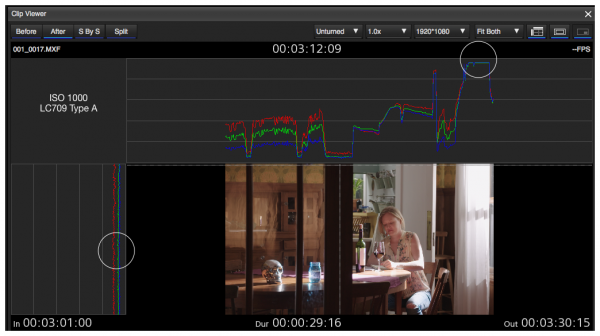

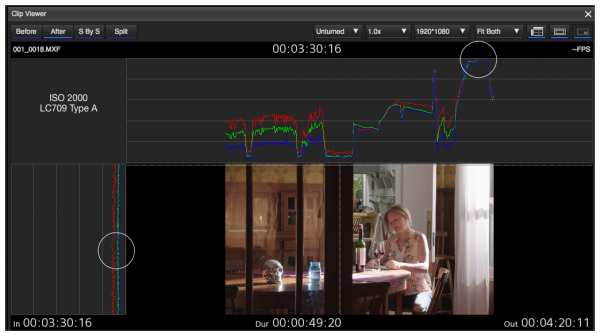

Pay attention to how highlight detail changes in the top right corner curtains as the ISO changes:

One of the key qualities of a camera is how it clips highlights. The FS7 does reasonably well in this regard. Highlights are neutral but they don’t roll off as gently as I’d like. When testing Alexa I discovered that its nominal Rec 709 curve places four stops of mid-tones between 17% and 80% on a waveform monitor. The F5/F55/FS7 LC709 Type A LUT puts five stops within this range, and I’ve often wondered whether it’s to make the highlight rolloff appear shallower than it is by compressing the tonal scale between middle gray and white clip. The FS7 doesn’t exactly hard clip in the highlights but it doesn’t roll off gently either. It falls somewhere in between. The top of the curve seems to flatten out aggressively.

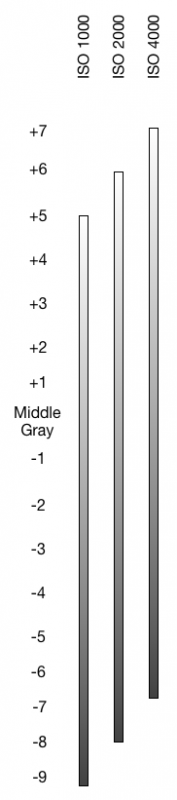

The FS7, like the F5 and F55, captures six stops of overexposure latitude above middle gray at ISO 2000, although the distribution of these stops changes based on ISO:

ISO 1000 gives us five stops from middle gray to white clip. ISO 2000 gives us six, and ISO 4000 gives us seven.

Noise and the number of stops visible between middle gray and white clip go hand in hand, so lets look at some combined waveforms below:

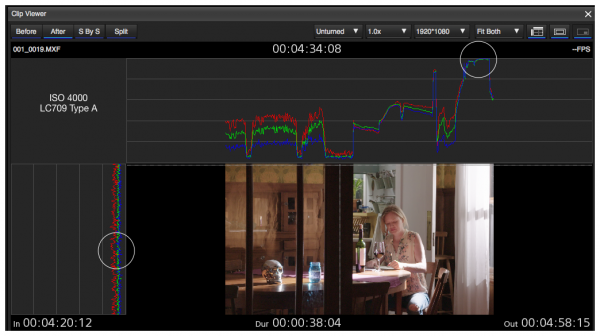

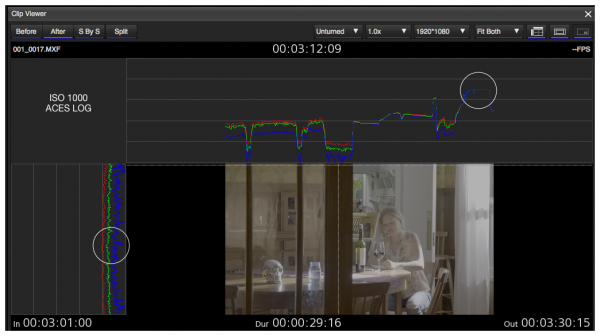

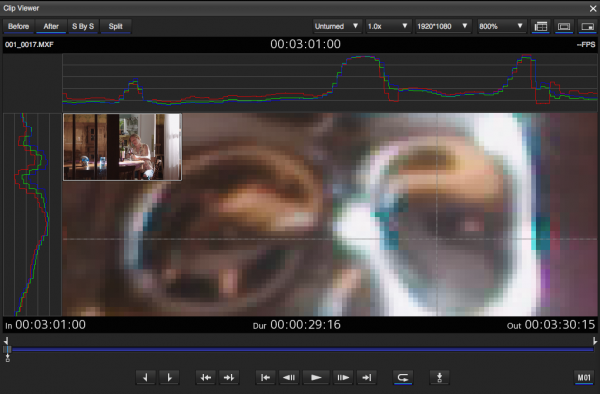

At ISO 1000 the top of the curtains is severely clipped, as seen in the waveform at the top of the screen. The waveform on the left is measuring noise along the vertical line in the center of frame, centered on the wooden frame of the pocket door, while the waveform above is measuring a single horizontal line of pixels at the top of the frame. Watch what happens to the width of the noise waveforms as we increase ISO. (NOTE: This curve clips at around 95% at ISO 1000.)

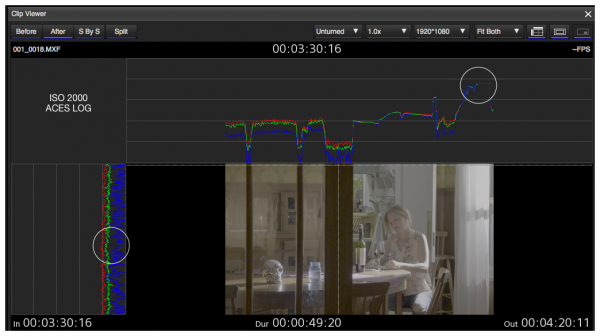

At ISO 200o we start to see a little detail in the scopes, although the top of the highlight curve is fairly compressed so it’s hard to see any additional detail in the curtains by eye. The noise waveform at left is noticeably wider than it was at ISO 1000, showing increased noise in the shadows. While Sony says that ISO 2000 is “native” for this camera, I don’t like noise in my images so I rate the camera at ISO 1000 when I can. (NOTE: This curve clips at a higher point, probably 98%. LUTs and log curves are mathematical functions, and at lower ISOs the values you feed in max out at a lower level so the function maps them lower. The higher the ISO the farther up the curve values are mapped.)

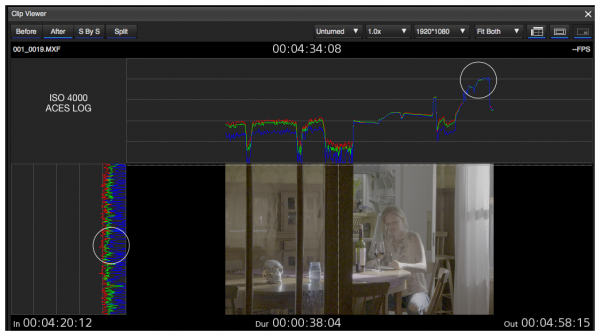

Lots of highlight detail becomes visible at ISO 4000, but the waveform on the left says that noise has increased considerably as well. This is always the tradeoff: highlight retention or amplified noise. NOTE: White is now clipping at 100%.

ISO 1000. The ACES Log curve flattens out the image but that’s because it is pushing data at the edges of exposure into the middle of the curve, making it easier to see what’s happening at the boundaries of exposure. The noise looks a lot more intense here but that’s just because it’s been amplified artificially by the log curve; I’ve found ISO 1000 to be very clean. Highlight information has been pulled down to the point where we can see every last bit of highlight detail in the scope. The LC709 Type A LUT wasn’t lying: the highlights are really clipped at this ISO.

ISO 2000. We’re starting to see a lot more highlight detail in the curtains, although the noise floor has taken a hit. The blue channel is a lot noisier, although that’s partly due to the wood having a warm hue (lacking in blue).

ISO 4000. We can now see almost all the highlight detail in the curtains, but the noise floor has come up considerably. I’ve shot at ISO 4000 on city streets at night, and while it’s not bad for certain things it’s definitely a look. It’s pretty noisy.

The top of the curtains appears to change in brightness between ISOs, but what we’re primarily seeing is the fact that the LUT maps maximum values to different signal values depending on ISO. You’re seeing the difference between a maximum white of 96% at ISO 1000 and 98% (ISO 2000) and probably 100% (ISO 4000). (The ISO 1000 value is accurate, but the others are rough guesses based on Sony Raw Viewer’s waveform calibration which appears to show 0-100% instead of 0-109%.) In the video clip section where I circle the highlight on the edge of the table, it’s difficult to see that higher ISOs are capturing more shadow detail because the highlight is also getting brighter as the maximum mapped highlight value increases.

I spotted something a little odd when I zoomed in to a highlight reference that Dan Drasin placed in the shot just for fun:

Those cyan specks are not so much blue/green as they are minus red, as you can see on the waveform above. Directly above each cyan spec the red channel plunges. Adam Wilt tells me that he’s seen this kind of artifact before, and it’s always on the trailing edge (right side) of clipped objects. His theory is that this is an artifact of the live deBayer process required to record it in real time to the internal cards. The externally recorded raw image doesn’t show these artifacts:

DeBayering after the fact, when processing power isn’t restricted by the speed at which frames must be processed, definitely has its advantages.

The camera outputs 12-bit log-encoded raw, similar what the FS-700 generates, and as best I can tell it looks pretty good. I say “pretty good” because I’m not totally sure what it does look like, due to the mismatch I mentioned above when recording SGamut3.cine/S-Log3 footage to an Odyssey that was expecting SGamut/S-Log2. When I pulled the footage into Resolve (Sony Raw Viewer doesn’t handle DNG files) I saw this:

Yikes! No amount of color correction in Resolve 11 could bring this back to normal. I got close when I changed the camera raw deBayer settings to the settings used by Blackmagic raw and maxed out the green gain, but I couldn’t bring the image to a place that matched the color in the XAVC footage. (I’m competent in Resolve, but I’m no seasoned colorist.)

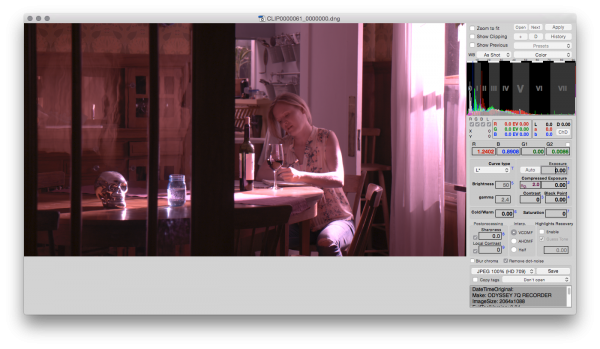

I have a number of still image DNG processing apps on my computer and I tried them all. The only one that worked was Raw Photo Processor 64. When I brought the image in it initially looked like this:

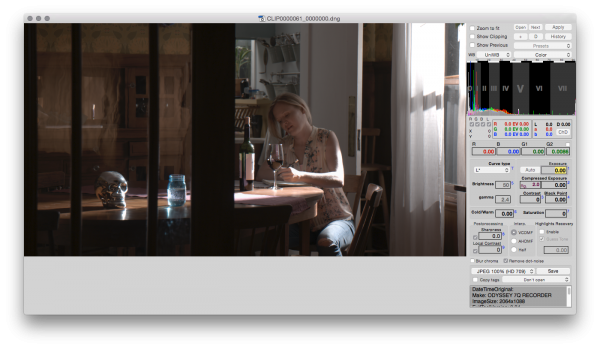

Changing the white balance from “As Shot” to “Unity WB” adjusted the red, green and blue gains from their original values of 1.24, 0.98 and 0 to 0, 0, 0, resulted in an image that was immediately gradable:

I’m still experimenting with these raw files as this raw converter app doesn’t contain a gamma curve option that’s plug-and-play for HD. It has an L* gamma curve that works very well but I don’t understand why: it appears to be some sort of linear-to-monitor gamma adjustment curve, but I can’t find any information on how it actually functions. I understand it’s popular as a monitor calibration standard for graphic designers in Europe.

According to Raw Photo Processor’s documentation, white balance happens at a very basic level when decoding raw footage, which begs the question as to why this was the only app I could find, in either the motion or still worlds, that allowed me to recover incorrectly recorded footage with one simple white balance adjustment.

The settings in Raw Photo Processor are somewhat complex the user interface takes some time to learn, but it seems this app could be useful as a last ditch effort to view and recover DNG images. It offers a batch conversion option that converts DNG files to full swing (full range) or studio swing (legal range) TIFF files in eight or sixteen bits, as well as a Rec 709 JPEG option.

The FS7’s highlight roll-off isn’t as gentle as I’d like, but it’s pretty good for a US$8,000 camera that sees in the dark and shoots slow motion up to 180fps. I prefer to rate the camera at ISO 1000 as I like clean, noise free images, but ISO 2000 isn’t bad and I’ve shot slow motion footage at night on city streets using only available light at ISO 4000 and nobody complained. Ultimately, though, the difference between the three ISO in handling the top stop or two of dynamic range isn’t that different: there’s a subtle difference, but it’s not huge.

I find XAVC a little limiting: I would never shoot any kind of visual effects work that required keying or rotoscoping to XAVC-I as edges are just too jagged and deBayering artifacts exist if you know where to look for them. Raw looks to be much higher quality, but without shooting it properly I don’t want to judge it critically. I suspect that most people will end up shooting in some flavor of XAVC, and for what the FS7 is—a small, light-weight light-sensitive camera with very pretty color and slow motion capabilities that’s great for handheld projects or non-VFX shoots with low budgets—it is by far the best in its class.

For the price this is a really versatile camera.

Thanks again to Dan Drasin and Jessica, Alan Hereford, Tom Guiney and Airbox Lighting, and especially Adam Wilt.